The Weekly Standard – In yet another installment of “nothing new under the sun,” the Fordham Institute has put out a survey-analysis assessing the controversial Common Core math standards. As the first of its kind, the survey of teachers’ reactions to the overhaul-alignment of American public schools is overdue and ultimately inconclusive. Results show the math standards are mostly working according to primary school teachers on the frontlines, not really working per middle school teachers—and not working at all according to parents on the homefront. Parents’ opinions are based on surveyed teachers’ reports of their interactions with parents. Full article is linked to below.

The study was conducted by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and was based on an online survey of a representative sample of 1,003 K–8 public school math teachers from the forty-three states plus the District of Columbia that had adopted (and retained) the Common Core State Standards for Mathematics as of March 2015. The excluded “nonadopting” states are Alaska, Indiana, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas, and Virginia. The survey was fielded between March 30 and May 15, 2015.

Key findings from the researchers:

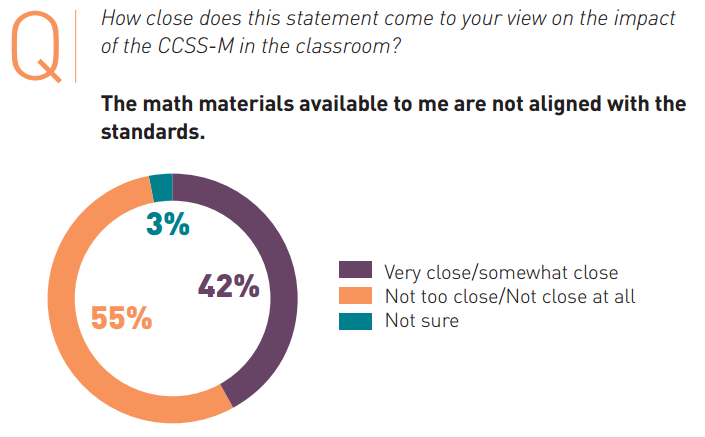

- Most teachers are partial to the Common Core, but they don’t think all of their students and parents are. Most teachers view the standards positively, believing that they will enhance their students’ math skills, prepare them to succeed in college, and bolster their ability to compete in a global economy. Further, most believe that the CCSS-M are an impetus for improving their own content knowledge. At the same time, teachers’ thoughts on the views of students and parents are considerably less rosy. They say that pupils are “frustrated” by having to learn multiple methods of solving a problem and worry that some have math anxiety, especially in grades 6–8. A whopping 85 percent say that “reinforcement of math learning at home is declining because parents don’t understand the way that math is being taught.” We know that teachers are the primary vehicle through which parents learn about the CCSS, so this raises a key question: How can they better help parents support their children’s success in math?

- Kids seem to be hitting a wall in middle school. Or, possibly, their teachers are. Overall, middle school teachers tend to have a more negative assessment of their students’ math abilities and the broader impact of the standards. We can’t know why. Perhaps it’s the obvious reason: Middle school standards are simply tougher than elementary standards. Perhaps it’s because more teachers in middle school have math degrees (versus elementary education degrees) and thus better grasp the math prowess needed in the upper grades. Or maybe it’s because today’s middle school students did not “grow up” with these standards in earlier grades, and the transition has been difficult. The logical question is this: If the latter is true, will this transition problem eventually work itself out? The researchers were surprised to find that elementary teachers tend to have more positive views of the potential benefits of CCSS-M and their impact on students. After all, we’ve heard many anecdotal reports of elementary teachers who feel that these standards are “developmentally inappropriate,” and it’s no secret that many primary teachers haven’t themselves studied a great deal of math. Yet 61 percent of K–2 teachers say they have fewer or about the same number of “students who have math anxiety” than before the CCSS-M, and 68 percent agree that “students are developing a stronger capacity to persevere in math and come up with solutions on their own.” It’s the middle school teachers who report more distress.

- Teaching multiple methods can yield multiple woes. The CCSS-M’s Standards for Mathematical Practice require that students “check their answers to problems using a different method.” And sure enough, 65 percent of K–5 teachers are teaching multiple methods more now than before the CCSS-M were implemented. Our focus group data and open-ended survey responses also reveal this to be one of the biggest lessons they’ve drawn from Common Core: Teach multiple ways to solve a problem. Makes sense to us. But this admonition has had COMMON CORE IN THE K-8 MATH CLASSROOM: RESULTS FROM A NATIONAL TEACHER SURVEY 6 ramifications for both students and their parents. One likely reason that math learning is suffering at home is that parents simply don’t know “multiple methods” themselves—they know the method they were taught two or three decades ago. Our authors recommend one solution (have students practice their preferred method at home), but surely there are other ways to teach students conceptual understanding without flummoxing them or their moms and dads.

- The math wars aren’t over. The Common Core math standards seek to bring a peaceful end to the “math wars” of recent years by requiring equal attention to conceptual understanding, procedural fluency, and application (applying math to real-world problems). Yet striking that balance has not been easy. We see in these results several examples of teachers over- or under-emphasizing one component to the detriment of another. A recent RAND study found the same thing and recommended that math teachers be given better guidance on how to balance the three areas in classrooms.

- Teachers are teaching Common Core math content at the grade levels that the CCSS-M specify. Though that may seem anticlimactic, it is noteworthy that teachers are able to identify from a list of topics (some of which are decoys) those that reflect the standards—and that they report teaching those topics at the grade levels where they’re supposed to be taught. This finding resonates with a study earlier this year by Thomas Kane and colleagues in which 85 percent of teachers reported having good or excellent knowledge of the standards for the grades and subjects that they teach.

Read the Article Survey Results (PDF, 1.5 MB)

Source: Thomas B. Fordham Institute

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute is the nation’s leader in advancing educational excellence for every child through quality research, analysis, and commentary, as well as on-the-ground action and advocacy in Ohio. It is affiliated with the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, and the publication referenced above is a joint project of the Foundation and the Institute. For further information, visit www.edexcellence.net . The Institute is neither connected with nor sponsored by Fordham University

What's your view?